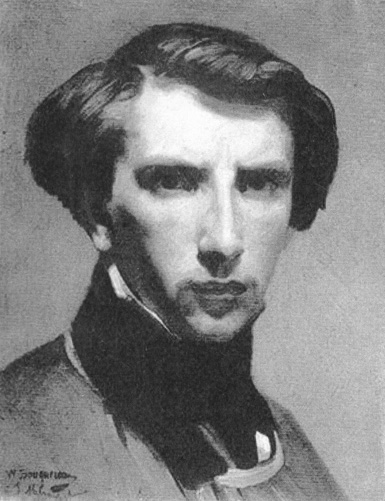

French Academic Classical Painter, Draftsman, and Teacher

1825 - 1905

"One has to seek Beauty and Truth, Sir! As I always say to my pupils, you have to work to the finish. There's only one kind of painting. It is the painting that presents the eye with perfection, the kind of beautiful and impeccable enamel you find in Veronese and Titian." --William Bouguereau, 1895

William-Adolphe Bouguereau was born in La Rochelle, France on November 30, 1825, into a family of wine and olive oil merchants. He seemed destined to join the family business but for the intervention of his uncle Eugène, a curate, who taught him classical and biblical subjects, and arranged for Bouguereau to go to high school. Bouguereau showed artistic talent early on and his father was convinced by a client to send him to the École des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, where he won first prize in figure painting for a depiction of Saint Roch. To earn extra money, he designed labels for jams and preserves.

Through his uncle, Bouguereau was given a commission to paint portraits of parishioners, and when his aunt matched the sum he earned, Bouguereau went to Paris and became a student at the École des Beaux-Arts. To supplement his formal training in drawing, he attended anatomical dissections and studied historical costumes and archeology. He was admitted to the studio of François-Edouard Picot, where he studied painting in the academic style. Academic painting placed the highest status on historical and mythological subjects and Bouguereau won the coveted Prix de Rome in 1850, with his Zenobia Found by Shepherds on the Banks of the Araxes. His reward was a stay at the Villa Medici in Rome, Italy, where in addition to formal lessons he was able to study first-hand the Renaissance artists and their masterpieces.

Bouguereau, completely in tune with the traditional Academic style, exhibited at the annual exhibitions of the Paris Salon for his entire working life.

Detail from The Birth of Venus by Bouguereau. An early reviewer stated, "M. Bouguereau has a natural instinct and knowledge of contour. The harmony and movement of the human body preoccupies him, and in recalling the happy results which, in this genre, the ancients and the artists of the sixteenth century arrived at, one can only congratulate M. Bouguereau in attempting to follow in their footsteps…Raphael was inspired by the ancients…and no one accused him of not being original."

Raphael was a favorite of Bouguereau and he took this review as a high compliment. He had fulfilled one of the requirements of the Prix de Rome by completing an old-master copy of Raphael'sThe Triumph of Galatea. In many of his works, he followed the same classical approach to composition, form, and subject matter.

In 1856, he married Marie-Nelly Monchablon and subsequently had five children. By the late 1850's, he made strong connections with art dealers, particularly Paul Durand-Ruel (later the champion of the Impressionists), who helped clients buy paintings from artists who exhibited at the Salons. The Salons annually drew over 300,000 people, thereby providing valuable exposure to exhibited artists. Bouguereau's fame extended to England by the 1860's and then he bought a large house and studio in Montparnasse with his growing income.

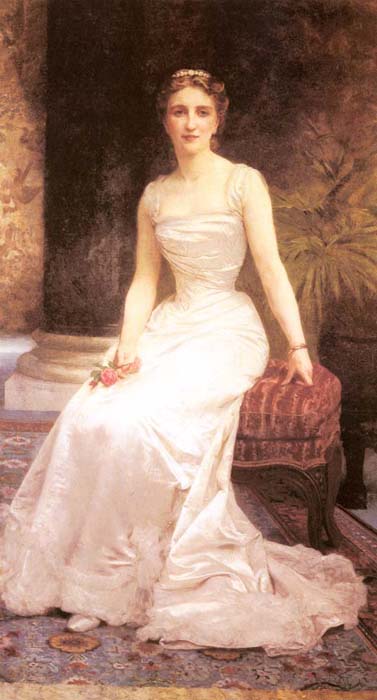

Bouguereau was a staunch traditionalist whose realistic genre paintings and mythological themes were modern interpretations of Classical subjects-both pagan and Christian-with a heavy concentration on the female human body. Although he created an idealized world, his almost photo-realistic style brought to life his goddesses, nymphs, bathers, shepherdesses, and madonnas in a way which was very appealing to rich art patrons of his time. The fact that his peasants always had clean feet, pristine clothes, and beautiful faces was totally acceptable to his admirers. Some critics, however, preferred the honesty of Jean-François Millet's truer-to-life depiction of hard-working farmers and laborers.

Bouguereau employed traditional methods of working up a painting, including detailed pencil studies and oil sketches, and his careful method resulted in a pleasing and accurate rendering of the human form. His painting of skin, hands, and feet was particularly admired. He also used some of the religious and erotic symbolism of the Old Masters, such as the "broken pitcher" which connoted lost innocence.

One of the rewards of staying within the Academic style and doing well in the Salons was receiving commissions to decorate private houses, public buildings, and churches. As was typical of these commissions, sometimes Bouguereau would paint in his own style, and other times he had to conform to an existing group style. Early on, Bouguereau was commissioned in all three venues, which added enormously to his prestige and fame. He also made reductions of his public paintings for sale to patrons, of which The Annunciation (1888) is an example. He was also a successful portrait painter though many of his paintings of wealthy patrons still remain in private hands.

Bouguereau steadily gained the honors of the Academy, reaching Life Member in 1876, and Commander of the Legion of Honor and Grand Medal of Honor in 1885. He began to teach drawing at the Académie Julian in 1875, a co-ed art institution independent of the École des Beaux-Arts, with no entrance exams and with nominal fees.

In 1877, both his wife and infant son died. At a rather advanced age, Bouguereau was married for the second time in 1896, to fellow artist Elizabeth Jane Gardner Bouguereau, one of his pupils. He also used his influence to open many French art institutions to women for the first time, including the Académie française.

He painted eight hundred and twenty-six paintings. Bouguereau died in La Rochelle at age 80 from heart disease. There can be little doubt that Bouguereau was one of the most talented painters of his time, but it is a shame that he has fallen into obscurity with museum curators and those supposedly sophisticated about art who think that ugliness and lack of content imply depth and talent.

As Damien Bartoli, world expert on Bougureau, points out: 'The beautiful and impassive young woman forms a truly modern icon, wearing a wreath of ears of corn decorated with flowers in the colors of the French nation: the blue corn-flower, white daisies and red corn poppies. At her feet lie strewn the symbols of agricultural France in the form of wheat and a grape vine, but also of an apple, symbolizing the autumn, the season of fruit and the harvest'. Alma Parens broke the world record for a Bougureau painting sold at auction in November of 1998 when it sold for $2,640,000, a record which was again broken a year and a half later with the sale of Charity for $3,600,000.

.jpg)

As an aside, consider this interesting article in the New York Times, published April 7, 2000, by KATIE HAFNER:

Lenn D. Lowry, the director of the Museum of Modern Art (let me repeat "the director of the Museum of Modern Art"), has a vivid memory of the first time he was profoundly moved by a work of art. At age 7, during a visit to the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass., he was separated from his parents.

While wandering in search of them, he came upon a huge painting, Nymphs and Satyr, by William Bouguereau. His parents found him a half-hour later, still staring at the 6-by-8-foot painting. "I just remember being completely transfixed by it," said Mr. Lowry, who is now 45.

The experience helped Mr. Lowry believe in the transformative power of art and what he calls the "unique encounters that occur when one is fortunate to confront directly an extraordinary object." Mr. Lowry, as well as other museum directors, wants to broaden the opportunity for such transforming moments by providing encounters with virtual art, viewed on a computer screen and brought to the art-viewing public via the World Wide Web.

And I have thrown my questions

so that it took them to you the wind...

... but you were stone

and the echo returned them to me...

Regardez les branches

Comme elles sont blanches,

Il neige des fleurs.

Riant de la pluie

Le soleil essuie

les saules en pleurs.

Et le ciel reflète

Dans la violette

Ses pures couleurs…

La mouche ouvre l'aile

Et la demoiselle

Aux prunelles d'or,

Au corset de guêpe

Dépliant son crêpe,

A repris l'essor.

L'eau gaiement babille,

Le goujon frétille

Un printemps encore !

Springtime

By Théophile Gautier

Look at the boughs,

How white they are,

It's snowing flowers!

Scoffing at the rain,

The sun dries

The weepy willow.

And the sky reflects

In the violets

Its pure colors…

The fly opens its wings

And the dragonfly

With the golden pupils,

And the wasp-like corset,

Unfolding its silky wings,

Has resumed its flight.

The water happily babbles,

The tiny fish wriggles

It's Springtime again!

You know, I'm not certain I've ever seen anything quite like this painting. It especially amazes me that a man drew this, not a woman.

In a way, isn't this how way every teenage girl has seen every teenage boy she ever had a crush on?

Symbolically she sits by "The Edge of the River". She sits at perhaps the greatest crossroads in life as she prepares to enter the adult world. Her hands and legs are crossed symbolically as are the trunks of the trees behind her. She wears a humanistic halo of vibrant red flowers alluding to the spirituality inherent in youth.

Gabriel Cot was the daughter of Bouguereau's most famous student, Pierre August Cot. Bouguereau was planning to use her for one of his major paintings, and so he started this as a study for that painting, but, as he worked, he was so captivated by Gabriel's beauty, including her intense inner beauty, that he finished it as one of his only un-commissioned portraits.

In Rome the Romans waved branches of laurel as a sign of joy and it adorned statues of Jupiter after every victory. The goddess of the Victory held a triumphal crown of laurel in one hand and in the other a palm branch. The winning generals, poets and scientists were crowned with it. Triumphant emperors wore laurel crowns and carried laurel in their hands. Emblem of peace and truce, carried on the victors javelin tips, it became a symbol of joy and victory. The use of crowns of laurel became so general that Christians used it to glorify their martyrs. Roman herdsmen scented and disinfected their cowsheds with fumigations of laurel mixed with sulphur and juniper. Doing the same in times of epidemic.

Daphne, pursued persistently by Apollo, implored the other Olympian gods to help her. By them she was rendered unrecognizable and changed into the most precious of aromatics, the laurel, whose light bark covered her breasts; her hairs became foliage, her graceful arms branches, her feet solid roots. Apollo, inconsolable, covers himself with leaves, and since, the name of 'Apollo's laurel' as remained.

The subjects of such pictures are usually simple people living in uncivilised conditions, featuring naïvety in their thinking and yet leading a happy and cheerful life. The style ignores the real misery associated with rural poverty. The approach to the presentation is not humorous, but emotional, sometimes sentimental.

When all continued to admire and praise Psyche's beauty but none desired her as a wife, Psyche's parents consulted an oracle, which told them to leave Psyche on the nearest mountain, for her beauty was so great that she was not meant for man. Terrified, they had no choice but to follow the oracle's instructions. But then Zephyrus, the west wind, carried Psyche away to a fair valley and a magnificent palace where she was attended by invisible servants until night fell and in the darkness of night the promised bridegroom arrived and the marriage was consummated. Cupid visited her every night to make love to her, but demanded that she never light any lamps, since he did not want her to know who he was.

Cupid even allowed Zephyrus to take Psyche back to her sisters and bring all three down to the palace during the day, but warning that Psyche should not listen to any argument that she should not try to discover his true form. The two jealous sisters told Psyche, then pregnant with Cupid's child, that rumor was that she had married a great and terrible serpent who would devour her and her unborn child when her time came for it to be fed. They urged Psyche to conceal a knife and oil lamp in the bedchamber, to wait till her husband was asleep, and then to light the lamp and slay him at once if it was as they said. Psyche sadly followed their advice. In the light of the lamp Psyche recognized the fair form on the bed as the god Cupid himself. However, she accidentally pricked herself with an arrow, and was consumed with desire for her husband. She began to kiss him, but as she did, a drop of oil fell from Psyche's lamp and onto Cupid's chest and he awoke. He flew away, and she fell from the window to the ground, sick at heart.

Psyche then found herself in the city where one of her jealous elder sisters lived. She told her what had happened, then tricked her sister into believing that Cupid had chosen her as a wife instead. She later met the other sister and deceived her likewise. Each returned to the top of the peak and jumped down eagerly, but Zephyrus did not bear them and they fell to their deaths at the base of the mountain.

Psyche searched far and wide for her lover, finally stumbling into a temple to Ceres where all was in slovenly disarray. As Psyche was sorting and clearing, Ceres appeared, but refused any help but advice, saying Psyche must call directly on Venus, the jealous shrew that caused all the problems in the first place. Psyche next called on Juno in her temple, but Juno, superior as always, said the same. So Psyche found a temple to Venus and entered it. Venus ordered Psyche to separate all the grains in a large basket of mixed kinds before nightfall. An ant took pity on Psyche and with its ant companions separated the grains for her.

Venus was outraged at her success and told her to go to a field where golden sheep grazed and get some golden wool. A river-god told Psyche that the sheep were vicious and strong and would kill her, but if she waited until noontime, the sheep would go to the shade on the other side of the field and sleep; she could pick the wool that stuck to the branches and bark of the trees. Venus next asked for water from the Styx and Cocytus flowing from a cleft that was impossible for a mortal to attain and was also guarded by great serpents. This time an eagle performed the task for Psyche. Venus, outraged at Psyche's survival, claimed that the stress of caring for her son, made depressed and ill as a result of Psyche's lack of faith, had caused her to lose some of her beauty. Psyche was to go to the Underworld and ask Persephone, the queen of the Underworld, for a bit of her beauty in a box that Venus gave to Psyche. Psyche decided that the quickest way to the Underworld would be to throw herself off some high place and die and so she climbed to the top of a tower. But the tower itself spoke to her and told her the route through Tanaerum that would allow her to enter the Underworld alive and return again, as well as telling her how to get by Cerberus by throwing him a cracker and Charon by paying him a golden coin, how to avoid other dangers on the way there and back, and most importantly to eat of no food whatsoever; for otherwise she would dwell forever in the Underworld. Psyche followed the orders explicitly and ate nothing while beneath the earth.

However when Psyche had got out of the Underworld, she decided to open the box and take a little bit of the beauty for herself. Inside, she could see no beauty; instead an infernal sleep arose from the box and overcame her. Cupid, who had forgiven Psyche, flew to her, wiped the sleep from her face, put it back in the box, and sent her back on her way. Then Cupid flew to Mount Olympus and begged Jupiter to aid them. Jupiter called a full and formal council of the gods, and declared it was his will that Cupid might marry Psyche. Jove then had Psyche fetched to Mount Olympus, and gave her a drink made from Ambrosia, granting her immortality. Although some say their daughter was named Bliss, and some say she was named Delight (in Roman mythology she was named Voluptas, which can mean either), the meaning of the name was intended to be joyful. Begrudgingly, Venus and Psyche forgave each other.

Alas, I would walk near her, yet be unnoticed,

Always at her side and always will be lonely.

Thus will I pass my time on this earth so weary

Daring to ask for nothing, nothing to receive.

She, whom God has made so sweet and tender,

Goes her absent-minded way hearing nothing

Of this murmur of love raised in her steps.

Piously dutiful, unswervingly faithful,

She will say, reading these verses so filled with her,

"Who is this woman?", and will never understand!

The poet Hesiod first represents him as a cosmic who emerged self-born at the beginning of time to spur procreation. The same poet later describes two love-gods, Eros and Himeros (Desire), accompanying Aphrodite at her birth from the sea-foam. Some classical authors interpreted this to mean they were born of the goddess at her birth, or alongside her in the sea-foam. The scene was particular popular in art, where the pair flutter around the goddess seated in her floating conch-shell.

Eventually Eros was multiplied by ancient poets and artists into a host of Erotes or Cupids, as they are commonly called in English. The one Eros, however, remained distinct in myth. It was he who lighted the flame of love in the hearts of the gods and men, armed either with a bow and arrows or else a flaming torch. He was also the object of cult. Eros was often portrayed as a child, the disobedient, but fiercely loyal, son of Aphrodite.

In ancient vase painting Eros is depicted as either a handsome youth or as a child. His attributes were varied: from the usual bow and arrows, to the gifts of a lover--a hare, a sash, or a flower. Sculptors preferred the image of the bow-armed boy, whereas mosaic artists favored the figure of a winged putto (plump baby).

Men say the gods have flown;

The Golden Age is but a fading story,

And Greece was transitory:

Yet on this hill hesperian we have known

The ancient madness and the ancient glory.

Under the thyrse upholden,

We have felt the thrilling presence of the god,

And you, Bacchante, shod

With moonfire, and with moonfire all enfolden,

Have danced upon the mystery-haunted sod.

With every autumn blossom,

And with the brown and verdant leaves of vine,

We have filled your hair divine;

From the cupped hollow of your delicious bosom

We have drunk wine, Bacehante, purple wine.

About us now the night

Grows mystical with gleams and shadows cast

By moons for ever past;

And in your steps, O dancer of our delight,

Wild phantoms move, invisible and fast.

Behind, before us sweep

Maenad and Bassarid in spectral rout

With many an unheard shout;

Cithaeron looms with every festal steep

Over this hill resolved to dream and doubt.

What Power flows through us,

And makes the old delirium mount amain,

And brims each ardent vein

With passion and with rapture perilous?

Dancer, of whom our votive hearts are fain,

You are that magic urn

Wherefrom is poured the pagan gramarie;

Until, accordantly,

Within our bardic blood and spirit burn

The dreams and fevers of antiquity.

.jpg)

"...He on his side

Leaning half raised, with looks of cordial love,

Hung over her enamoured, and beheld

Beauty which; whether waking or asleep,

Shot forth peculiar graces; then with voice,

Mild as when Zephyrus on Flora breathes,

Her hand soft touching, whispered thus: 'Awake!

My fairest, my espoused, my latest found,

Heaven's last, best gift, my ever-new delight.'"

Zephyrus (the West wind), who was fond of Hyacinthus and jealous of Apollo, blew Appolo's arrow off course to kill Hyacinthus (since she was mortal) Zephyrus was also in love with Flora (a Goddess).

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

TO possess strong feelings and amiable affections, and to express them with a nice discrimination, has been the attribute of many female writers; some of whom have also participated with the author of Psyche in the unhappy lot of a suffering frame and a premature death. Had the publication of her poems served only as the fleeting record of such a destiny, and as a monument of private regret, her friends would not have thought themselves justified in displaying them to the world. But when a writer intimately acquainted with classical literature, and guided by a taste for real excellence, has delivered in polished language such sentiments as can tend only to encourage and improve the best sensations of the human heart, then it becomes a sort of duty in surviving friends no longer to withhold from the public such precious relics.

The copies of Psyche printed for the author in her lifetime were borrowed with avidity, and read with delight; and the partiality of friends has been already outstripped by the applause of admirers.

The smaller poems which complete this volume may perhaps stand in need of that indulgence which a posthumous work always demands when it did not receive the correction of the author. They have been selected from a larger number of poems, which were the occasional effusion of her thoughts, or productions of her leisure, but not originally intended or pointed out by herself for publication.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.