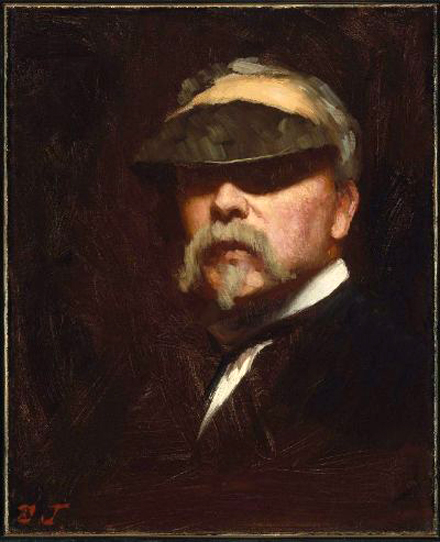

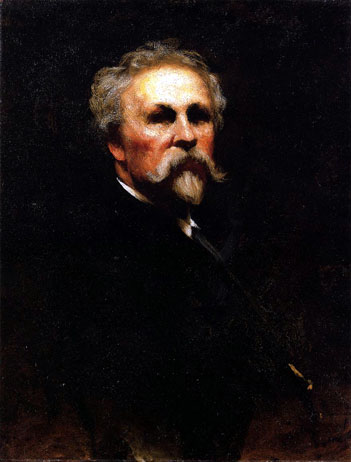

American Painter

1824 - 1906

Eastman Johnson

Self Portrait: ca 1890

Eastman Johnson was an American painter, and Co-Founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, with his name inscribed at its entrance. Best known for his genre paintings, paintings of scenes from everyday life, and his portraits both of everyday people, he also painted portraits of prominent Americans such as Abraham Lincoln, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. His later works often show the influence of the 17th century Dutch masters whom he studied while living in The Hague, and he was even known as The American Rembrandt in his day.

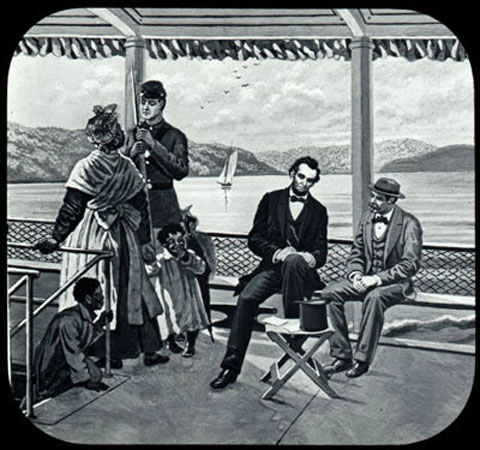

Illustration of Abraham Lincoln as he sits on a bench and writes a draft of the

Emancipation Proclamation in the 1860's.

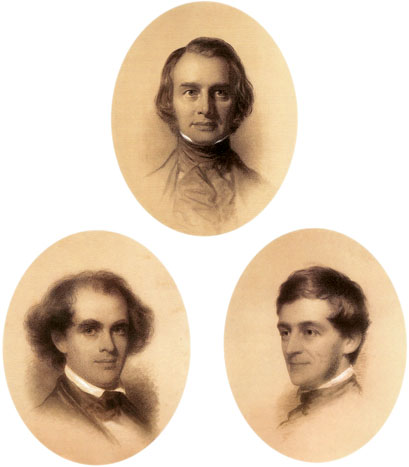

Eastman Johnson's: Longfellow, Hawthorne, and Emerson

Johnson was born in Lovell, Maine, the eighth and last child of Philip Carrigan Johnson (Secretary of State of Maine 1840, and Mary Kimball Chandler (born in New Hampshire, 18 October 1796, married 1818). His eldest brother Commodore Philip Carrigan Johnson Jr.

Philip Carrigan Johnson Jr (1876)

.jpg)

Eastman Johnson - his brother, Commodore Philip Carrigan Johnson - (father of Vice Admiral Alfred Wilkinson Johnson) was followed by his beloved sisters Harriet, Judith, Mary, Sarah, Nell and his brother Reuben. Eastman grew up in Fryeburg and Augusta, where the family lived at Pleasant Street and later at 61 Winthrop Street.

His career as an artist began when his father, the owner of several businesses, Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of Maine (ancient Free and Accepted Masons), Secretary of State for Maine was appointed by US President James Polk, after his patron the Governor of Maine John Fairfield entered the US Senate, as Chief Clerk in the Bureau of Construction, Equipment, and Repair of the Navy Department. From 1853, the family lived at 266 F Street, between Thirteenth and Fourteenth Streets and just a few blocks from the White House and the Navy Department Offices, Washington DC. His father apprenticed him in 1840 to a Boston lithographer. In 1849 he moved to Düsseldorf, Germany where many artists, including many Americans, studied Art, and there was accepted into the studio Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, a German who had lived in the United States for a while before returning to Germany. Johnson then moved to The Hague and studied 17th century Dutch and Flemish masters. He ended his European travels in Paris, studying with the academic painter Thomas Couture in 1855. After returning to America in 1855 due to the death of his mother. In 1857 he lived and painted among the native Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) near Superior, Wisconsin. In 1859, he established a studio in New York city and secured his reputation as an American artist with an exhibition featuring his painting Negro Life at the South or as it is more popularly known Old Kentucky Home.

Negro Life in the South: 1859

Johnson fills a scene set in a Washington, D.C., backyard with African Americans who enact virtually every phase of family life: courtship and marriage, motherhood, training the young, and listening to the elderly. Focusing on the black community, he marginalizes the white visitor at the right. Johnson seems to have sought a measure of ambiguity in recounting his tale. Such open-ended story lines would characterize many postwar paintings of everyday life. Although the location is urban, he called the painting Negro Life at the South, which invited viewers to see the tenements as outbuildings on a plantation. On the eve of the Civil War, apologists for slavery could read Johnson's narrative for signs of easy living and family solidarity despite forced servitude. Abolitionists could interpret the dilapidated buildings and humbly dressed people as symbols of slavery's oppression of blacks.

Quoted From: American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life - Special Exhibitions - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

He was also a member of the Union League Club of New York, which holds many of his paintings.

On his death, Eastman Johnson was buried at Green Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

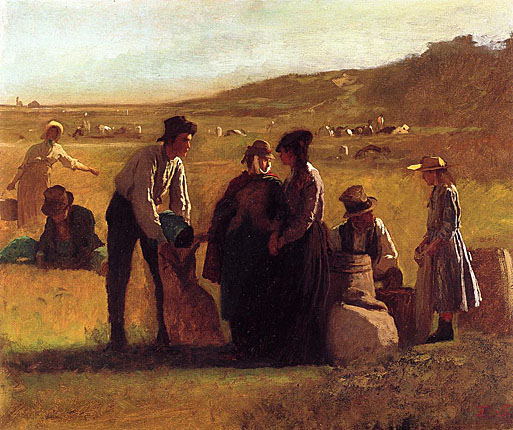

Johnson's style is largely realistic in both subject matter and in execution. His original photorealistic charcoal sketches were not strongly influenced by period artists, but are informed more by his lithography training. Later works show influence by the 17th century Dutch and Flemish masters, and also by Jean François Millet. Echoes of Millet's The Gleaners can be seen in Johnson's The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket although the emotional tone of the work is far different.

The Gleaners: 1857

by Jean François Millet

The Gleaners (Des glaneuses) is an oil painting by Jean-François Millet composed in 1857. It depicts three peasant women gleaning a field of stray grains of wheat after the harvest. The painting is famous for monumentalizing what were then the lowest ranks of rural society. The painting was received poorly by the French upper class.

Quoted from: "The Gleaners" Wikipedia. 2010. Wikimedia Foundation Inc.

Cranberry Pickers, Nantucket: ca 1879

The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket: 1880

In 1870, after searching for aspects of American rural life to use as subjects for ambitious paintings, Johnson began to draw inspiration from Nantucket Island, in Massachusetts. With this view of a cranberry harvest, he successfully realized his efforts to paint a celebration of New England outdoor life.

The work also marks a significant achievement in the history of American art. Using an evocative, rather than descriptive, technique, Johnson lavishes attention on the landscape, from the dry grasses of the cranberry bog to the distant and accurate view of Nantucket's spires and lighthouse. The principle focus of this scene washed by late-afternoon light is the configuration of pickers, and their poses and gestures. The standing woman in the center who looks at a boy carrying an infant to her creates a narrative suggesting that the artist recorded the scene as he witnessed it.

Quoted From: Timken Museum: Eastman Johnson

Comparison: The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket - 1879 and 1880

His careful portrayal of individuals rather than stereotypes enhances the realism of his paintings. Ojibwe artist Carl Gawboy notes that the faces in the 1857 portraits of Ojibwe people by Johnson are recognizable in people in the Ojibwe community today. Some of his paintings such as Ojibwe Wigwam at Grand Portage display near photorealism long before the photorealism movement but in keeping with the American tradition of realism that can be seen in the works of Charles Willson Peale whose painting The Stairway Group is said to have fooled George Washington.

Washington Crossing the Delaware

by Eastman Johnson

(Eastman Johnson, "Washington Crossing the Delaware",

Copy after Emmanuel Leutze Original, Private Collection/Art Resource)

One is astonished in the study of history at the recurrence of the idea that evil must be forgotten, distorted, skimmed over. We must not remember that Daniel Webster got drunk but only remember that he was a splendid constitutional lawyer. We must forget that George Washington was a slave owner . . . and simply remember the things we regard as creditable and inspiring. The difficulty, of course, with this philosophy is that history loses its value as an incentive and example; it paints perfect men and noble nations, but it does not tell the truth (W.E.B. Dubois).

History cannot give us a program for the future, but it can give us a fuller understanding of ourselves, and of our common humanity, so that we can better face the future (Robert Penn Warren).

History is not history unless it is the truth (Abraham Lincoln).

Quoted From: Our Epic History Center

This has less to do with Eastman Johnson as it is an editorial comment by Senex Magister.

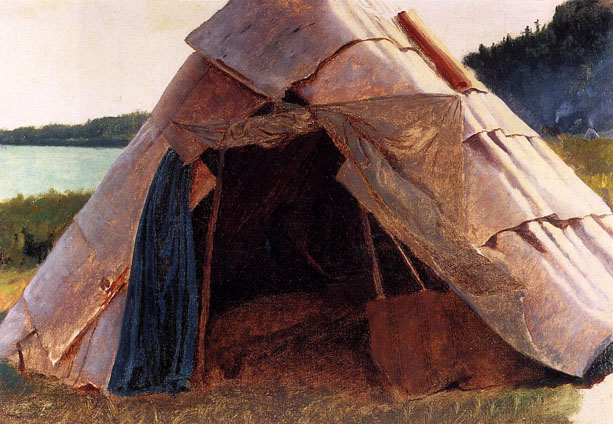

Ojibwe Wigwam at Grand Portage: 1857

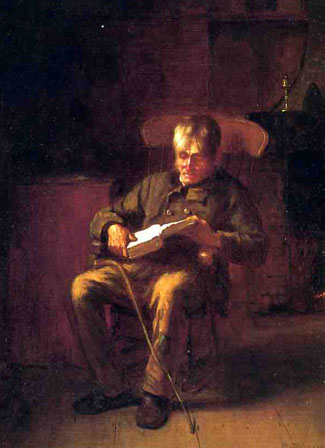

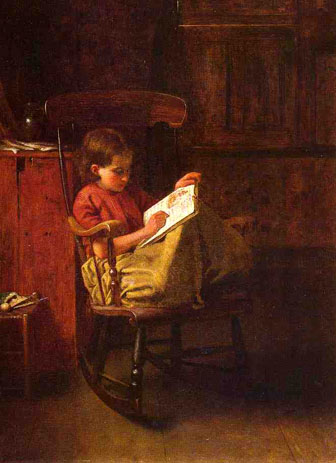

His careful attention to light sources contributes to the realism. Portraits Girl and Pets and The Boy Lincoln make use of single light sources in a manner that echoes the 17th Century Dutch Masters.

Girl and Pets: 1856

© The Corcoran Gallery of Art/CORBIS

A Child's Menagerie: 1859

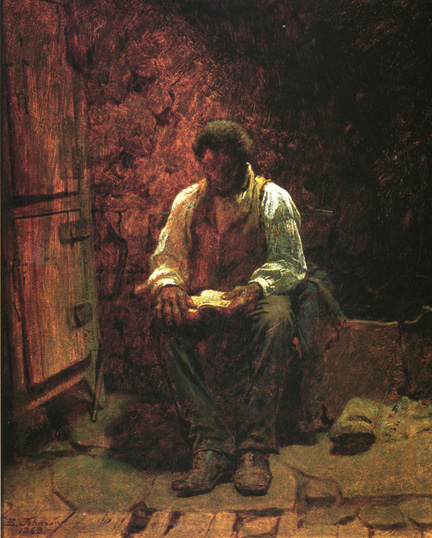

The Boyhood of Abraham Lincoln: 1868

The Boy Lincoln was painted by Eastman Johnson in 1868. It was executed oil on canvas and measures 46 x 37 inches. It is in the permanent collection at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, Michigan. The subject matter is the young Abraham Lincoln who is captured reading a book by the light from the nearby fire. Johnson created a number of paintings where children were reading or writing predicting the future success of these intellectually engaged youths.

Quoted From: Eastman Johnson: The-Boy-Lincoln

Jonhson's subject matter included portraits of the wealthy and influential from the President of the United States, to literary figures to portraits of unnamed individuals, but he is best known for his genre work, his paintings of everyday people in everyday scenes. Johnson often repainted the same subject changing style or details.

William Hayes Fogg: 1887

William H. Fogg (1817-1884), China Trader, and Berwick Academy's Fogg Memorial

Grover Cleveland

Title: Oil Portrait of Grover Cleveland

Description: Always known for his immense stature, President Grover Cleveland looks formidable in this portrait. The president cherished time away from the public, and so had a second residence built for his family near the nation's capital. Furthermore, few renovations of the White House were needed after President Arthur left office.

Date: 1891

Painter: Eastman Johnson

Quoted From: White House Historical Association (White House Collection)

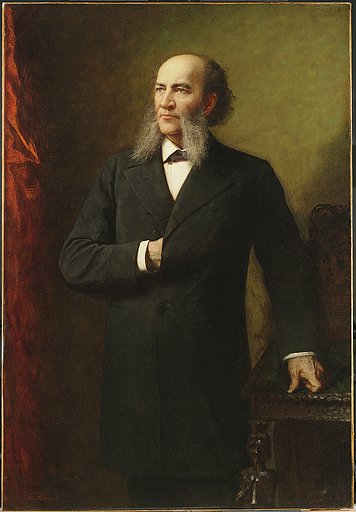

Benjamin Harrison

Title: Oil Portrait of Benjamin Harrison

Description: President Benjamin Harrison was the grandson of President William Henry Harrison. In 1891, electricity was installed in the Harrison White House, and all the gas chandeliers were replaced with electric light fixtures. President Harrison also held afternoon receptions in the East Room for all the public to attend, regardless of race.

Date: 1895

Painter: Eastman Johnson

Quoted From: White House Historical Association (White House Collection)

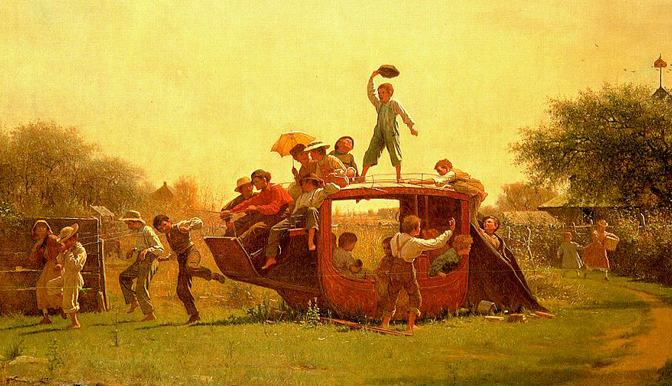

His depictions of New England life, such as The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket (see above), The Old Stagecoach, Husking Bee, Island of Nantucket, The Sap Gatherers, and Sugaring Off at the Camp, Fryeburg, Maine established him solidly as a genre painter. Over the course of five years, he made many sketches and smaller paintings depicting the process of turning maple sap into maple sugar, but never completed the larger work he had started.

The Old Stagecoach

THE OLD STAGECOACH by Jonathan Eastman Johnson - CHILDREN

Husking Bee, Island of Nantucket: 1876

Sugaring Off at the Camp - Fryeburg, Maine: ca 1864-66

The Maple Sugar Camp, Turning Off: ca 1865-73

Sugaring Off: The Maple Sugar Paintings of Eastman Johnson

In contrast, the much celebrated Old Stagecoach was mostly staged in his studio and its composition carefully planned. The stage coach itself originated as an abandoned coach that he encountered and sketched while hiking in the Catskills. The children were painted from local children recruited from near his Nantucket Studio. Despite this artifice, the painting was celebrated as wholesome, natural and bucolic.

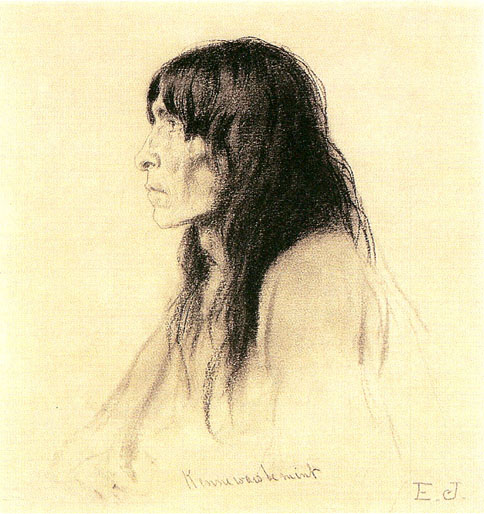

After his return from Europe, Johnson went to visit his sister in what was then the western frontier of Wisconsin. Carl Gawboy, a modern day Ojibwe artist, has posited that Johnson's guide was likely George Bonga, a son of Pierre Bonga, a freed slave, who had married an Ojibwe woman. Gawboy speculates that Johnson's time with this mixed-race family changed his approach to painting. Certainly Johnson was successful in getting many Ojibwe to sit for him. His drawings and painting depict Ojibwe people in a much more intimate and relaxed manner than is usual for painting of that period. Also unusual was that he often included the subject's names in the title of the works. He did not focus solely on individual portraits, but also did paintings and sketches of scenes which including the Ojibwe dwellings, Saint Louis bay, and other groupings of Ojibwe in everyday activities.

Kay be sen day way We Win

Eastman Johnson: Paintings and Drawings of the Lake Superior Ojibwe

Kenne waw be mint

Johnson left Wisconsin due to wide spread financial panic that rendered his real estate investments there worthless. He left there for Cincinnati, Ohio to make money via portrait commissions and did not return to the subject of the Ojibwe. His paintings and sketches of the Ojibwe remained unsold during his lifetime and now are in the possession of the Tweed Museum of Art on the campus of University of Minnesota Duluth.

Negro Life at the South is considered Johnson's masterpiece. Although this painting was popularly known as Old Kentucky Home nearly from the beginning, it depicts a scene from Washington, D.C.

Negro Life at the South

The painting is a domestic scene behind a dilapidated house. On the right in the foreground is a couple courting, in the middle there is a banjo player playing while an adult woman dances with a child as others look on. One of the onlookers, far to the right is a young white woman in an elegant white dress. Above the scene, an adult woman looks out a window as she steadies a small child sitting on the partially collapsed roof. Skin tones vary in the scene from person to person. Aside from the white observer on the far right, the palest person in the scene is the young woman being courted. The darkest skin belongs to the woman dancing with the child in the middle foreground. Some have viewed this as simple realism, others see it as an invitation to the viewer to contemplate the mixed racial heritage of those portrayed. Both proponents and detractors of slavery have seen this painting as defending their positions.

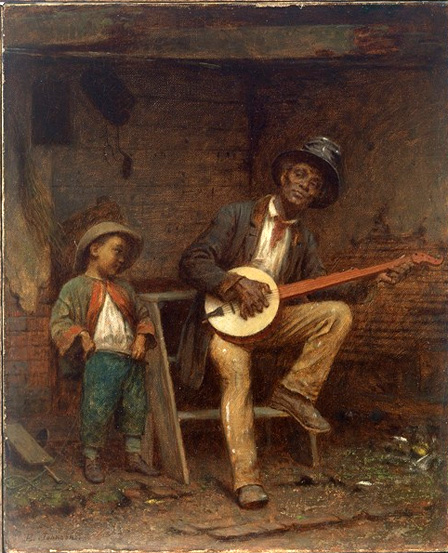

Confidence and Admiration: ca 1859

In "Confidence and Admiration", a scene of a slave playing the banjo in the company of an admiring young boy, Eastman Johnson repeated the central figure group from his well-known "Negro Life at the South" (New-York Historical Society). Painted in 1859, this complex painting of slaves in an interior yard next to the Johnson family home in Washington, D.C. became the century's best-known image of American slaves and launched the artist's career when he showed it in New York later that year. Both versions of Johnson's depiction of slave camaraderie and music-making might appear nostalgic and romantic. But, as abolitionist (and former slave) Frederick Douglass emphasized to readers of his autobiography (1845): "Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy."

Quoted From: Five College Museums/Historic Deerfield Collections Database

Another painting of Johnson's is less open to interpretation.

A Ride for Liberty - The Fugitive Slaves painted in 1862, depicts a slave family riding to freedom. This painting is based on Johnson's observations during the Civil War battle of Manassas.

A Ride for Freedom - The Fugitive Slaves: ca 1862

Various Other Works of Eastman Johnson

A Boy in the Maine Woods: ca 1868

A Day Dream: 1877

A Quiet Hour: 1873

A Sly Drink at the Camp

_ca1860_73.jpg)

A Rustic Courtship: ca 1866

An Earnest Pupil

(aka The Fifers): 1881

_1881.jpg)

At the Camp, Spinning Yarns and Whittling: ca 1864-66

At the Maple Sugar Camp: 1870

Babes in the Woods: 1882

Barn Swallows: 1878

Eastman Johnson's depictions of rural life appealed to a widespread sense of nostalgia in the American post-Civil War era. "Barn Swallows" is one of several similar subjects he produced in 1877 and 1878 while visiting his sister, Harriet May, and her family at their summer home in Kennebunkport, Maine. Though New Yorkers, the May children and their friends represent a rustic ideal of childhood on the farm. The restless children perch inside a shadowy barn on a summer day, illuminated only indirectly by sunlight reaching into the space. A cast-off book and an abandoned bouquet tell of the diversions that fill their happy days.

Quoted From: Philadelphia Museum of Art

Cachette: ca 1867

Camp Scene at Grand Portage: 1857

Captain Folger of Nantucket: 1880

Captain Nathan H. Manter: 1873

Catching the Bee: 1872

Catching Up on the News: Date Unknown

Children Reading: Date Unknown

Christmas Time

(aka The Blodgett Family): 1864

_1864.jpg)

Copy after Jules Breton's 'Le Depart les Champs':ca 1865

Corn Husking: 1860

Cranberry Pickers: ca 1879

Dinah, Portrait of a Negress: ca 1866-69

Eastman Johnson's Dinah, Portrait of a Negress joins the Gibbes' collection as a visual representation of the strength of enslaved African-Americans and augments the Museum's collection of work that preserves and illustrates this chapter in American history. The subject of the painting is thought to be modeled after abolitionist Harriet Tubman, who helped over 300 slaves escape the oppression of the South via the Underground Railroad during her lifetime. The painting is currently on view on the first floor of the Gibbes as part of the ongoing exhibition Art in the South: the Charleston Perspective.

Quoted From: Gibbes Museum of Art Announces New Acquisition

Dropping Off: 1873

Ethel Eastman Johnson Conkling: Date Unknown

Ethel Eastman Johnson Conkling with Fan: ca 1895

Feather Duster Boy: 1880

Feeding the Lamb: ca 1875

Fiddling His Way: 1866

This is an oil on canvas painting of a black fiddler - a freedman - who performs in the kitchen of a rural white family. The musician, on the left side of the canvas, fiddles, while the family of ten watches. The three young boys are gathered closest to the fiddler, while the mother stands with a laughing infant in her arms, a young girl stands by her right side and yet another young girl site on the floor, across from the musician. Behind the mother, the farmer himself is seated on a box holding something; a grown-up daughter stands with broom in hand behind the farmer, while a older woman scrubs a plate in the background. The kitchen appears dark.

Quoted From: Chrysler Museum of Art - Norfolk, VA

Fiddling His Way: 1866

An itinerant musician entertains a family in the dim interior of their rustic dwelling in Eastman Johnson's "Fiddling His Way". Elders and children alike are enthralled by the fiddle's simple tunes: on the right, a tall young woman listens as she leans against the doorway, her broom idle in her hand, and even the baby in its mother's arms at the center of the image reaches out toward the fiddler, providing a counterweight to the reserved, pipe-smoking farmer. The small room in which the figures are crowded is furnished with the practical implements of everyday life, but such details are subordinated to the figures, their softly modeled features evincing their quiet attention to the music.

The itinerant artist or musician was a popular theme in American genre paintings, or scenes of everyday life, created in the first half of the nineteenth century. A common inspiration for these works was the famous "Blind Fiddler", a painting by Scottish artist David Wilkie (1785-1841), as demonstrated by Philadelphia artist John Lewis Krimmel's work of the same title in the Terra Foundation's collection. Johnson's painting shares with these earlier works the shallow, stage-like setting of a crowded farmhouse interior, the placement of the seated musician on the left, and the range of figure types representing both sexes and all ages. But his interpretation eschews their studied attention to telling detail and their atmosphere of merriment. Drawing on his first-hand study of such Dutch seventeenth-century masters as Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and his training in Paris under the French painter Thomas Couture (1815-1879), Johnson rendered objects and figures as emerging in indefinite contours from the shadowy, confined space they occupy. Their dull earth tones and muted reds complement the painting's mood of quiet contentment and retrospection: the scene is not so much a slice of ordinary life as an evocation of an earlier time, when harsher material realities were countered by simpler pleasures.

"Fiddling His Way" is one of two works of this title painted the same year. The Terra Foundation's painting may be a study for the other, more elaborate, and larger version (Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia), but the latter differs in several significant respects, notably in showing the fiddler as an African American. It belongs to a group of paintings Johnson made in the Civil War era on the theme of the life and prospects of American blacks on the eve of slavery's abolition. When he substituted an elderly white fiddler for the black player, however, Johnson signaled his increasing artistic interest in rural New England life. Like the cranberry harvesting and maple sugar processing he portrayed in the 1860's and 1870's, the entertainment provided by the traveling fiddler is presented as an antiquated and endangered tradition in a rapidly changing America.

Quoted From: Terra Foundation for American Art

Five Boys on a Wall: ca 1871

Gathering Lilies: 1865

During the 1860's and 1870's Eastman Johnson was one of America's leading specialists in genre paintings. He spent the early years of his career painting portraits, primarily in Boston and Washington, but in 1849 decided to enroll in the prestigious art academy at Düsseldorf, Germany. There he studied with the history painter Emanuel Leutze, who provided superb instruction in the fundamentals of composing multi-figure subjects. Johnson subsequently spent three years in The Hague, where he made careful study of the works of the Dutch old masters, and then moved to Paris to train in the studio of Thomas Couture, another accomplished history painter.

Johnson returned to America in 1855 and settled in New York. He quickly established a reputation as a genre painter, using the technical skills he had learned in Europe to create masterful works such as "Old Kentucky Home-Life in the South", 1859 (New-York Historical Society). During the mid-1860's, he turned his attention to painting idealized views of women in various pursuits; his masterpiece among these is the beautiful "Gathering Lilies". A solitary woman is shown bending down to pick the flower of a water lily from the surface of a tranquil pond with her right hand while holding other flowers in her left. Johnson perfectly captured the graceful elegance of her motion as she balances on the log and turns to grasp the stem of the flower. By using a close vantage point looking slightly downward and eliminating a view toward a distant horizon, he created an intimate environment of the pond and its banks, establishing the woman as the focus of the image.

Quoted From: National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Girl at the Window: ca 1871-79

Girl in Barn

(aka Sarah May): ca 1877-78

_ca_1877_78.jpg)

Hannah amidst the Vines: 1859

Hannah: ca 1859

Head of a Black Man: ca 1868

Hiawatha: 1857

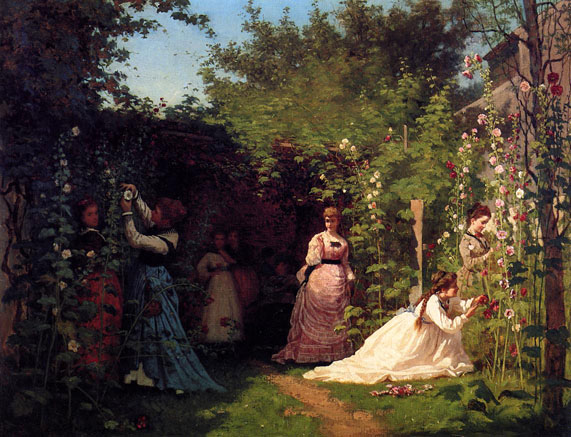

Hollyhocks: 1874-76

The subject of women in an enclosed garden has a long tradition in art history. The enclosed garden, or hortus conclusus, was traditionally associated with the Garden of Eden, a theme with potent implications for artists of the New World, which was often referred to as the "New Eden." It was also identified with the purity of the Virgin Mary, and many late-nineteenth-century artists extended this analogy to women in general. An evocative floral language developed to suggest the fertility and beauty of the female sex. In Hollyhocks the flowers stand as tall as the women, their lyrical swaying attitudes mirroring the grace of their human counterparts. The women, like the hollyhocks, are arranged decoratively along the periphery of the compound, and the red, pink, and white of their gowns are the colors of hollyhock blooms. Enclosing the hollyhocks-and, by extension, the women-within the confines of a walled garden allowed them the benefits of air and light without exposing them to the dangers of the rapidly modernizing world. From this sheltered position, both the women and the flowers in Hollyhocks become beautiful, but passive, objects of contemplation.

Quoted From: Eastman Johnson

Ice Skater: 1879

In the Hayloft: ca 1877-78

Interior of a Farm House in Maine: 1865

Kitchen at Mount Vernon: 1857

Lighting His Pipe: ca 1860

Little Girl with Red Jacket Drinking from Mug: Date Unknown

Lunchtime: ca 1865

Man in a Cornfield: Date Unknown

Man with Scythe: 1868

Measurement and Contemplation: ca 1861-63

Mother and Child: 1869

Mother and Child: Date Unknown

Musical Instinct: 1860-69

Negro Boy: 1860

Not at Home: ca 1873

The painting's title may seem curious, especially since there is clearly someone in this comfortably furnished domestic interior. In the past, however, the phrase "not at home" indicated that the occupants of the house were not available to receive visitors. This painting held a particularly personal meaning for Eastman Johnson; it is his wife, Elizabeth, whom we see climbing the stairs leading to more private areas of their residence on Manhattan's West Fifty-fifth Street.

Quoted From: Brooklyn Museum: American Art

Old Man, Seated: ca 1880-85

On Their Way to Camp: 1873

During the early 1860's genre painter Eastman Johnson made numerous trips to Maine from his home in New York to create studies of men and women working at maple sugar camps. His intention was to produce a large genre painting that would rival history paintings in scale and ambition, but he never succeeded in completing the work and set the project aside in 1865. The subject of "On Their Way to Camp" was derived from his early studies of the camps. Although his interests had previously centered on the busy activities of making the sugar, here he shows two boys towing a sled with a sap barrel through snowy woods; a third, younger boy rides atop the barrel and holds a wooden bucket. The trees around them have been tapped to gather the maple sap, and in the background is a glimpse of a wooden lean-to and the red flames of a fire.

Quoted From: National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Portrait of a Child: 1879

Portrait of a Woman: 1881

Portrait of Captain Charles Myrick: 1879

Portrait of James G. Wilson: 1876

Portrait of Mrs. Eastman Johnson: ca 1888

Portrait of Vinnie Packard: 1882

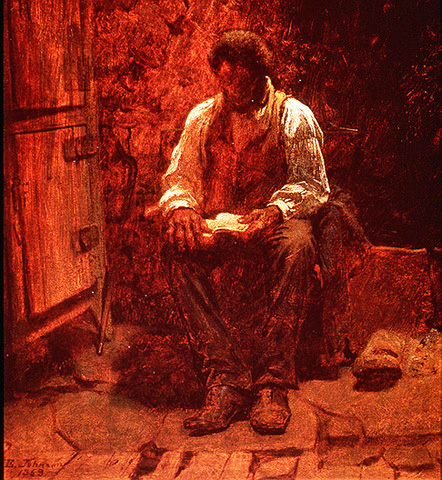

Reading the Bible: 1863

This contemplative, well-ordered interior, with light filtering in through the curtained window, shows the strong influence of Dutch masters like Vermeer. Johnson would have had many opportunities to study their work during his almost four-year stay in the Netherlands.

Quoted From: Currier Collections Online

Ruth: ca 1880-85

Sanford Robinson Gifford: 1880

Sarah Osgood Johnson Newton: 1856

Setting the Trap: 1863

Sharpening the Scythe: ca 1865

Shoemaker Haberty's Shop: ca 1887

Study for A Glass with the Squire: ca 1880

Study for The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket: ca 1879

Sunday Morning (aka The Evening Paper): 1863

_1863.jpg)

Sunday Morning: 1866

Susan Ray's Kitchen, Nantucket: 1875

The Boston Rocker: Date Unknown

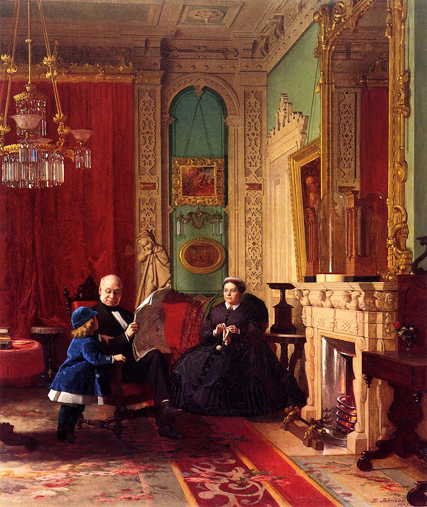

The Brown Family: 1869

The Card Players: 1853

The Chimney Corner: 1863

The Confab: Date Unknown

The Conversation: 1879

The Counterfeiters: ca 1853

The Early Lovers: Date Unknown

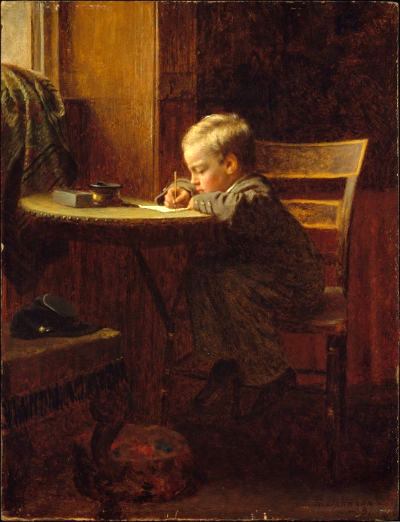

The Early Scholar

The Freedom Ring: 1860

The Funding Bill, Portrait of Two Men: 1881

The Girl I Left Behind Me: 1881

The young woman in this picture called "The Girl I Left Behind Me" by Eastman Johnson may be the most passionate portrayal in all nineteenth-century American art. It is even more openly romantic than Winslow Homer's pictures of women. Everything about her is animated by an inner intensity. She combines the majesty of a classical statue with the mood of a tragic heroine.

Who is she and what inspired Johnson to paint her? We have no answers, which contributes to the mystery of the picture. We do know that Johnson thought enough of this large painting to send it to major exhibitions in Chicago, Brooklyn, and Philadelphia in 1875 and 1876. The catalogues suggest that it was owned by the artist, and not for sale. It was still in Johnson's possession-along with several other ambitious and important pictures-when he died in 1906.

Quoted From: Director's Choice - The Girl I Left Behind Me

The Hatch Family: 1871

The Lesson

(aka The Lesson with Page N. O. P. of the Alphabet Book): 1874

_1874.jpg)

The Little Convalescent: ca 1872-80

During the 1870's, Johnson frequently visited his sister Harriet May and her family, who spent summers on a farm in Kennebunkport, Maine. He often used Harriet's children as models, capturing their carefree play. "The Little Convalescent" is probably a picture of Harriet reading to one of her children, who is sick in bed-his condition alluded to by the medicine bottles, thermometer, bell, and toothbrush in the background. While Harriet concentrates on the book, caring for her son's mind as well as his body, the little boy turns to look at the artist. Johnson painted a number of pictures of children reading or writing, to suggest they would grow up to be thoughtful, responsible adults. The best known of these depicts the boy Abraham Lincoln-who would serve as United States president during the Civil War-reading by firelight. "The Little Convalescent" is also one of several tender pictures of mothers nurturing their children that Johnson was inspired to paint after the birth of his only child in 1870.

Quoted From: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Lord is My Shepherd: ca 1863

Eastman Johnson painted "The Lord Is My Shepherd" only months after the Emancipation Proclamation of New Year's Day, 1863. The image of a humble black man reading from his Bible was reassuring to white Americans uncertain of what to expect from the freed slaves. But the simple act of reading was itself a political issue. Emancipation meant that blacks must educate themselves in order to be productive, responsible citizens. In the slaveholding South, teaching a black person to read had been a crime; in the North, the issue was not "May they read?" but "They must read."

Quoted From: The Smithsonian American Art Museum

The Savoyard Boy: 1853

The Little Soldier: Date Unknown

Wounded Drummer Boy

Eastman Johnson drew his inspiration for this Civil War picture from an incident that reportedly occurred during the Battle of Antietam (1863) in which an injured drummer boy asked a comrade to carry him so that he could continue drumming his unit forward. The emblematic image of a heroic youth literally rising above the chaos of the battlefield resonated deeply with Northern audiences both during and after the war. Johnson's initial drawing of the subject was exhibited in 1864 to foster support for the army, and the finished painting of 1871-for which this work is a preparatory study-helped to commemorate the hope and sacrifice of the Union effort. In this study, the loose brushwork, bright highlights, and lack of detail powerfully evoke the experience of battle-the steady drum beat, the smoke-filled air, and the drama of life and death.

Quoted From: Brooklyn Museum: American Art

Union Soldiers Accepting a Drink

Civil War Symbolism by Nona Martin

Winnowing Grain: ca 1873-79

The Civil War left America irrevocably changed. Men who had fought in some of the bloodiest battles ever known now faced the challenge of returning to everyday life, while grieving for the fallen. Artists often turned to metaphors of harvest and reaping to address these great losses. The mood underlies this peaceful image of a man, who may have been a soldier, separating chaff from the stream of corn that pours from his bucket.

Quoted From: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

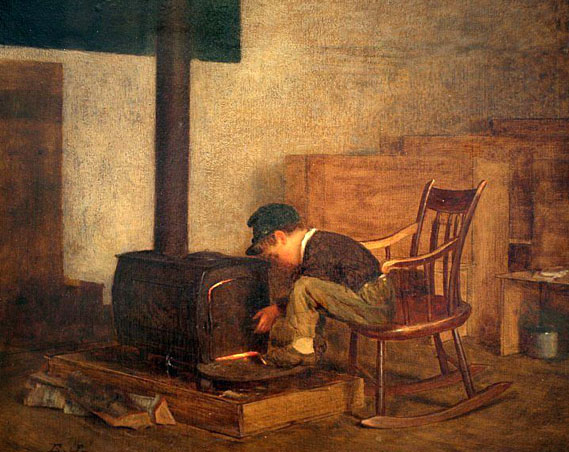

Writing to Father: 1863

The families of those at the front often yearned for news of loved ones, scouring the published lists of dead and wounded and writing many letters. Here a boy, brow furrowed with concentration, writes to his faraway father. The left-behind army cap that rests on the chair poignantly evokes the absent father.

Quoted From: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Self-Portraits of Jonathan Eastman Johnson

Man with a Hat

(aka Self Portrait): 1853

_1853.jpg)

Self Portrait: 1863

Self Portrait with Bottle of Champagne: 1863

Self Portrait: ca 1860

Self Portrait: ca 1885

Self Portrait: ca 1890

Self Portrait: Date Unknown

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Eastman Johnson Online

Source: The Athenaeum

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.